-

缨翅目 (Thysanoptera) 和膜翅目 (Hymenoptera)昆虫的繁殖采用单倍−二倍体性别决定系统(Haplodiploid sex-determinationsystem)。雌虫行两性生殖时,受精卵发育成二倍体雌虫,未受精卵发育成单倍体雄虫;而产雄孤雌生殖(Arrhenotoky)的后代全为单倍体雄虫[1-3]。它们的性别分配可用多种理论模型来表征[4],其中,常用的模型有局域配偶竞争(Local mate competition)理论[5]和获精受限雌虫模式(Constrained females model)[6]。这2种模型的背后隐含着一个重要的假设前提:雌虫能感知和评价周边环境的信息,然后对子代性比进行调节[4]。普通大蓟马(Megalurothrips usitatus) 是一种植食性蓟马,主要为害豆科植物的嫩芽、花朵和嫩荚等器官[7-11]。在我国海南,该虫已成为豇豆(Vigna unguiculata)的头号害虫[12]。跟很多植食性蓟马一样,普通大蓟马采用两性生殖和产雄孤雌生殖方式来繁衍后代[7,9,12]。蓟马的性比受很多因素的影响,包括蓟马的生物学和生态学特性、温度、食物和防控因子等[3,13-15]。雌虫通过控制受精囊内精子的输入和释放来调控子代性比[16]。蓟马性比的调节可分为2个部分,即交配期间的性比调节和交配后的性比调节[12]。迄今,有关同种成虫对蓟马交配期间性比调节的影响尚未见报道。本研究将评价同种成虫的气味对普通大蓟马雌虫交配和子代性比的干扰作用,旨在明确该虫在交配期间能否利用气味来判别周边同种成虫的性别和交配状况,然后调控雌虫获得精子的能力,进而对子代性比进行调节。

-

在网室大棚内种植豇豆(Vigna unguiculata)(品种:‘纯丰’长豇豆),按常规栽培措施进行管理。选取健康的幼嫩豆荚作为饲养普通大蓟马的食物。

-

在海南大学海甸校区植物保护学院教学实验基地(110°32′E,20°05′N),采集豇豆花朵内的普通大蓟马成虫,于室内以幼嫩豇豆豆荚饲养。饲养条件设定为(26±1)℃、相对湿度(60±5)%、光周期L(光照时间)∶D(黑暗时间)= 14∶10。待子代化蛹后,挑蛹,单头饲养于玻璃试管(12 mm×100 mm)内。成虫羽化后,立即按性比1∶1 进行配对饲养。部分刚羽化的雌虫仍继续单头饲养。最后,挑选健康的、特定日龄的、已交配或未交配的雌虫或雄虫作为试虫。

-

共设4个处理。①对照(无气味源):无成虫;②已交配雌虫气味源:6头已交配的2日龄雌虫;③未交配雌虫气味源:6头未交配的2日龄雌虫;④已交配雄虫气味源:6头已交配的2~3日龄雄虫。实验条件设定为(26±1)℃、相对湿度(60±5)%、光周期L∶D= 14∶10。

在聚丙烯果蝇管(24 mm×95 mm)底部的中央开1个透气圆孔(直径15 mm),并用0.043 mm尼龙网封孔。用透明硅胶管(内径22 mm×20 mm)将2支果蝇管从管底侧对接起来,作为气味试验装置,其中,1支管作为气味源管,另1支为被测试虫管。在每支果蝇管内放置1个盛有1 mL 10%蔗糖水的离心管管盖(内径14 mm),管盖被封口膜封住,管盖口朝下。接着,往气味源管释放试虫(对照无试虫),再用硅胶塞堵住管口。在被测试虫管中接入1头刚羽化的雌虫,并用硅胶塞堵管口;3 h后再接入1头刚羽化的雄虫,再堵塞管口。最后将已接虫的气味试验装置放入平躺的密封玻璃罐(2 100 mL)中,每罐放置1个实验装置。每处理重复数为19~25。

被测试虫配对24 h后,将雌虫从被测试虫管中挑出,然后转移到试管(12 mm×100 mm)中进行单头饲养,管内有一段幼嫩豆荚,并用棉球封管口。每24 h更换豆荚,直至雌虫死亡。将更换出来的旧豆荚移到新的试管中继续饲养,适时补充幼嫩豆荚,直至子代成虫羽化。每天观察和记录试管内子代雄虫和雌虫的数量,并计算子代性比(即雄性占成虫比例)。

-

利用Excel 2010 进行试验数据处理和绘图;利用SPSS 19.0 软件进行试验数据的统计分析。性比数据经反正弦转换后,进行方差分析(ANOVA)和多重比较(Duncan多重比较法,P<0.05)。

-

用不同气味源处理配对的普通大蓟马24 h后,被测雌虫所产子代的雄虫数、雌虫数和成虫数都有不同程度的变化(表1)。

表 1 同种成虫的气味处理配对期间的普通大蓟马对子代成虫数量的影响

气味源 子代成虫数/头 雄虫 雌虫 成虫 对照 16.55±2.36ab 38.09±3.09a 54.64±3.29ab 已交配雌虫 21.04±1.52a 22.80±1.67b 43.84±2.48b 未交配雌虫 13.32±1.63b 46.95±4.97a 60.26±6.49a 已交配雄虫 14.39±1.71b 45.35±4.56a 59.74±5.39a 注:表中数值为平均数±标准误,同一列数据后标有不同字母表示在P<0.05上差异显著。 子代雄虫数:对照、已交配雌虫气味处理、未交配雌虫气味处理和已交配雄虫气味处理的子代雄虫数分别为16.55、21.04、13.32和14.39头,其中,已交配雌虫气味处理与未交配雌虫气味处理和已交配雄虫气味处理之间的差异达到了显著水平(P<0.05)。

子代雌虫数:已交配雌虫气味处理的子代雌虫数最少,仅为22.80头,跟其他处理均有显著差异(P<0.05)。另3个处理的子代雌虫数介于38.09~46.95头,但彼此之间无显著差异。

子代成虫数:子代成虫数最少的处理仍是已交配雌虫气味处理(43.84头),与未交配雌虫气味处理和已交配雄虫气味处理之间的差异均达到了显著水平(P<0.05),但与对照(54.64头)相比差异不显著。

-

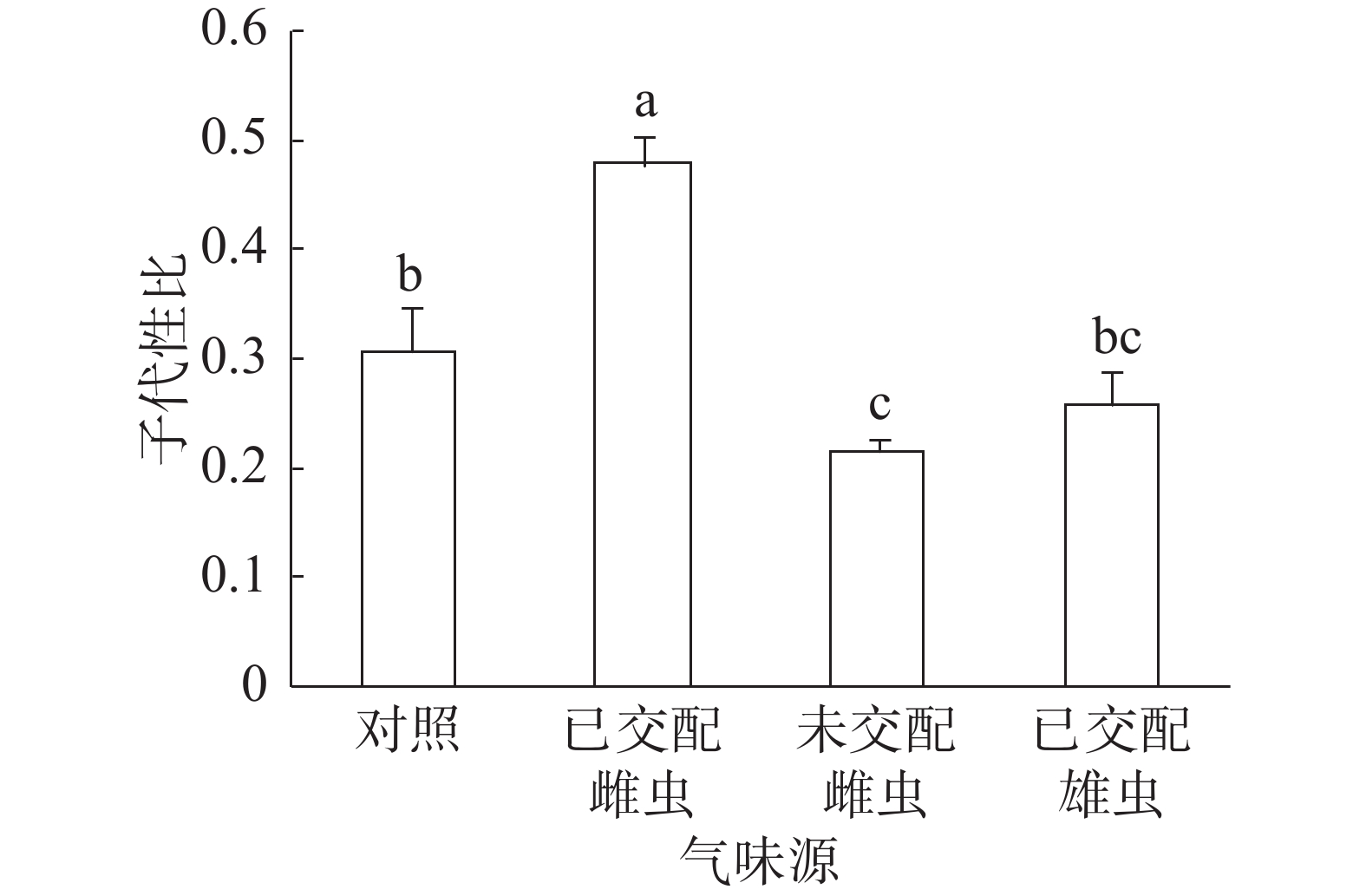

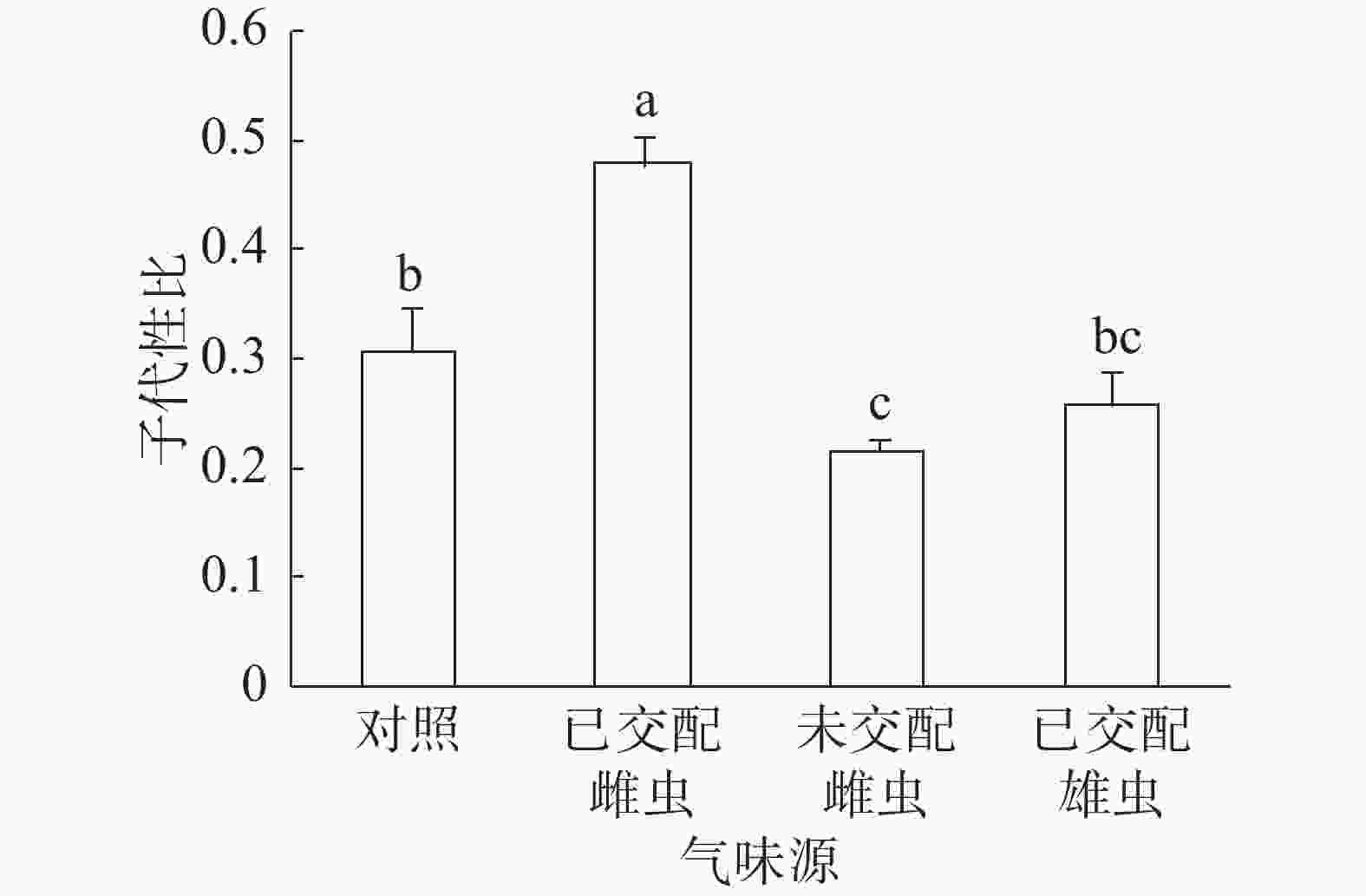

子代性比:普通大蓟马子代性比的响应随成虫气味源而异(图1)。已交配雌虫气味处理的子代性比高达0.48,同其他3个处理之间的差异均达到显著水平(P<0.05)。未交配雌虫气味处理的子代性比最低,仅为0.22,跟对照(0.31)差异显著(P<0.05)。已交配雄虫气味处理的子代性比(0.26)比对照的子代性比略低,两者之间没有显著差异。

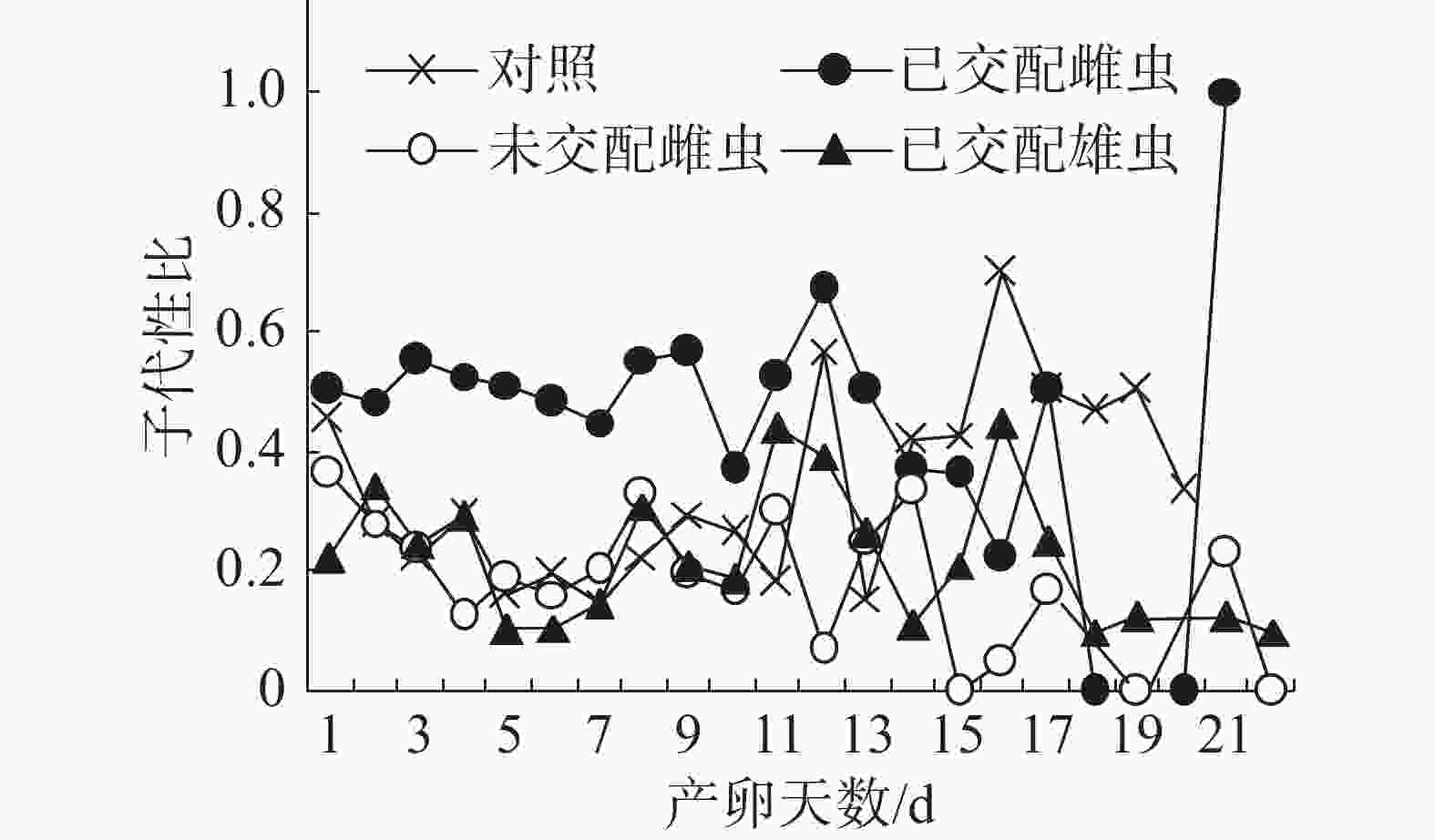

子代性比日变化:在不同气味处理条件下,普通大蓟马子代的日性比均呈现波动性(图2),其中,已交配雌虫气味处理的子代性比日变化别具特色。从图2可知,在雌虫产卵观测期的第1~13天,已交配雌虫气味处理的日性比介于0.37~0.67,多数接近0.50,但均大于对照;随后日性比变化趋势出现反转,从产卵第14天至第20天,对照的日性比大于已交配雌虫气味处理;至产卵第21天时,已交配雌虫气味处理的日性比达到1.00,即所产子代全为雄虫,意味着雌虫受精囊内的精子已消耗殆尽。对照、未交配雌虫气味处理和已交配雄虫气味处理的日性比波动范围分别为0.15~0.7、0.00~0.33和0.10~0.44。在产卵第1~11天,未交配雌虫气味处理和已交配雄虫气味处理的日性比波动类似于对照。但是,从在产卵第12天起,这3个处理的日性比波动呈现出不一样的态势。

-

各种气味处理条件下,被测雌虫的产卵天数平均值介于11.52~12.96 d,彼此之间没有显著差异,表明同种雌虫和已交配雄虫的气味对雌虫产卵期都没有明显影响。

-

有关同种成虫对单倍−二倍体昆虫性别分配的影响的研究常常侧重于评价相伴雄虫或雌虫对已交配雌虫子代性比的干扰作用,例如,美棘蓟马(Echinothrips americanus)[17-18]和多种寄生蜂[19-23],而对同种成虫如何影响交配期间的性别分配鲜有报道。本研究首次探究普通大蓟马交配期子代性比调节对同种成虫气味的响应。结果表明,已交配雌虫气味能使雌虫调高子代性比;未交配雌虫气味则导致雌虫降低子代性比,性比更加偏雌;已交配雄虫气味对子代性比调节没有影响。

昆虫交配期间性别分配的关键在于雌虫是否能够获得足够数量的优质精子[4]。雌虫的获精能力取决于以下3个方面:①雄虫的精子供应能力:雄虫所产精子的数量与质量跟雄虫的大小、年龄、交配次数和高温胁迫等因素有关[24-26]。②交配持续时间的长短:通常精子转移的数量随交配时间的延长而增加[27]。③精液蛋白(Seminal fluid proteins)的数量与质量:通过交配转移到雌虫体内的精液蛋白能降低雌虫再次交配率,提高产卵量[25,28-29]。事实上,雌虫除了掌控受精囊内精子的释放外,还参与了精子的输入[21,27]。在本研究中,被测试虫是刚羽化的成虫,4个处理在实验条件方面的差异仅限于气味源的不同。所以,已交配雌虫气味对普通大蓟马子代性比的干扰效果很可能与交配持续时间的缩短有关,尽管本研究没有交配时间的观测数据。在已交配雌虫气味处理条件下,普通大蓟马子代雌虫数仅为对照的60%,在雌虫产卵最后1天的子代全为雄虫,说明转移到雌虫体内的精子数量是不够的。

雌虫的气味谱在交配前后会发生变化,这为昆虫种群内成员判别雌虫的交配状况提供了1个可能途径[30]。对膜翅目昆虫中某些种类的研究表明,未交配雌虫与已交配雌虫的气味谱的确存在差异。未交配雌蜂释放的是对雄蜂具有吸引力的性信息素,对求偶和交配有利。与之相反,已交配雌蜂往往释放具有驱避作用的信息素,其中包括随精液传递到雌虫体内的抑性欲信息素(Antiaphrodisiacs)[31-32],这类信息素具有以下主要功能:避免雄虫的骚扰;阻止雄虫的求偶与交配行为,防止雌虫再次交配,进而避免出现精子竞争[33-36]。对蓟马而言,涉及雌虫信息素的研究比较少。据报道,美棘蓟马[37]和西花蓟马(Frankliniella occidentalis)[38]雄虫能判别同种雌虫的交配状况,很可能与抑性欲信息素有关。但是,跟普通大蓟马同一个属的非洲大蓟马(Megalurothrips sjostedti)雄虫对雌虫的交配状况无辨别能力[39]。迄今为止,关于蓟马雌虫信息素的鉴定仅有1篇报道。有报道称美棘蓟马雌虫能释放挥发性信息素,该信息素对产卵率具有抑制作用[40]。本研究揭示,已交配普通大蓟马雌虫的气味还有另1个功能,即影响同种其他雌虫的交配和性别分配。结合非洲大蓟马的相关信息,笔者推测,已交配普通大蓟马雌虫的气味组分中可能不含抑性欲信息素,对交配期间的性别分配起作用的信息素是雌虫自己合成的,不来自雄虫。在未来,有必要对已交配普通大蓟马雌虫的信息素展开进一步研究,雌虫信息素的研发可为普通大蓟马绿色防控探索出1条新的途径。蓟马雄虫信息素的研究主要聚焦于聚集信息素,目前已有多种蓟马的聚集信息素被分离与鉴定[41],其中,包括普通大蓟马[42-43]和非洲大蓟马[44]。在本研究中,已交配雄虫气味对普通大蓟马子代性比没有干扰作用,由此说明,雄虫所释放的聚集信息素对该虫交配期间的性别分配没有贡献。

Offspring sex ratio response to odors from conspecific adults in Megalurothrips usitatus (Bagrall)(Thysanoptera:Thripidae)

-

摘要: 为了探究同种成虫的气味对普通大蓟马(Megalurothrips usitatus)交配期间性比调节的影响,设置对照(无气味)、已交配雌虫、未交配雌虫和已交配雄虫等4种气味源,分别处理单对刚羽化成虫24 h,然后用幼嫩豇豆(Vigna unguiculata)豆荚单头饲养被测雌虫,观测每日所产子代的性别和数量,计算子代性比。结果表明:已交配雌虫气味处理的子代雌虫数(22.80头)最少,跟其他处理差异显著。同对照的子代性比(0.31)相比,已交配雌虫和未交配雌虫的气味分别导致子代性比显著提高和降低,子代性比分别为0.48和0.22,而已交配雄虫气味对子代性比无显著影响。4个处理中,仅已交配雌虫气味处理的雌虫在产卵最后1天的日性比达到1.00,即雌虫体内的精子已消耗殆尽。成虫气味源对雌虫产卵天数没有明显影响。实验结果说明,普通大蓟马在交配期间能依靠嗅觉判别周边雌虫的交配状况,然后通过调控雌虫的获精数量,实现对子代性比的自调节。Abstract: To explore the effects of odors from conspecific adults on sex ratio adjustment during mating by bean flower thrips, Megalurothrips usitatus, one of main pests on Vigna unguiculata . In this paper, a pair of newly emerged male and female of the been flower thrips was exposed for 24 hours to the odors from 6 mated females, 6 virgin females, 6 mated males and no adult as control, respectively. Then the focal female was transferred to a glass tube containing a section of a young cowpea pod for her feeding and oviposition. The pod was replaced daily until the focal female died. The pod containing eggs was transferred to a new glass tube for the offsprings’ growth. Oviposition days of the focal females were recorded, and their adult offspring were sexed and counted. Sex ratios of offspring were calculated as proportion of males. The results showed that the number of female offspring per focal female for the treatment with the odor from mated females was 22.80, being significantly less than those for other treatments. The sex ratios of adult offspring produced by the thrips treated with the odors from mated and virgin females were 0.48 and 0.22, respectively, which both were significantly different from that of control (0.31). The odor from mated males, however, showed no significant effect on offspring sex ratio. The daily sex ratio at the last oviposition day for the focal females treated with the odor from mated females reached 1.00, suggesting that their sperms had been depleted. The oviposition days of the focal females did not differ among all treatments. Our research revealed that the bean flower thrips during mating can use olfactory cues to assess mating status of conspecific females, and then control the number of sperms transferred into spermathecae, thereby adjusting sex ratio of their offspring.

-

Key words:

- Megalurothrips usitatus /

- cowpea pods /

- arrhenotoky /

- sex allocation /

- olfactory cues

-

表 1 同种成虫的气味处理配对期间的普通大蓟马对子代成虫数量的影响

气味源 子代成虫数/头 雄虫 雌虫 成虫 对照 16.55±2.36ab 38.09±3.09a 54.64±3.29ab 已交配雌虫 21.04±1.52a 22.80±1.67b 43.84±2.48b 未交配雌虫 13.32±1.63b 46.95±4.97a 60.26±6.49a 已交配雄虫 14.39±1.71b 45.35±4.56a 59.74±5.39a 注:表中数值为平均数±标准误,同一列数据后标有不同字母表示在P<0.05上差异显著。 -

[1] MORITZ G. Structure, growth and development[M]//LEWIS T. Thrips as crop pests. Wallingford: CAB International, 1997: 15 − 63. [2] DE LA FILIA A G, BAIN S A, ROSS L. Haplodiploidy and the reproductive ecology of arthropods [J]. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 2015, 9: 36 − 43. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2015.04.018 [3] BONDY E C, HUNTER M S. Sex ratios in the haplodiploid herbivores, Aleyrodidae and Thysanoptera: A review and tools for study[M]//JURENKA R. (ed.). Advances in Insect Physiology, Cambridge: Academic Press, 2019, 251 − 281. [4] WEST S. Sex allocation[M]. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2009: 14 − 378. [5] HAMILTON W D. Extraordinary sex ratios [J]. Science, 1967, 156(3774): 477 − 488. doi: 10.1126/science.156.3774.477 [6] GODFRAY H C J. The causes and consequences of constrained sex allocation in haplodiploid animals [J]. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 1990, 3(1/2): 3 − 17. [7] 张念台. 蓟马为害杂粮之习性及其防治[J]. 中华昆虫特刊, 1987(1): 55 − 72. [8] 范咏梅, 童晓立, 高良举, 等. 普通大蓟马在海南豇豆上的空间分布型[J]. 环境昆虫学报, 2013, 35(6): 737 − 743. [9] TANG L D, YAN K L, FU B L, et al. The life table parameters of Megalurothrips usitatus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on four leguminouscrops [J]. Florida Entomologist, 2015, 98(2): 620 − 625. [10] 谭珂, 李曼娟, 陈鑫, 等. 普通大蓟马产卵选择性初探[J]. 热带作物学报, 2015, 36(3): 587 − 590. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-2561.2015.03.024 [11] 谭珂, 陈鑫, 李曼娟, 等. 普通大蓟马在3种豆类作物上的实验种群生命表研究[J]. 热带作物学报, 2015b, 36(5): 956 − 960. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-2561.2015.05.021 [12] 罗亚丽, 施丹, 乔雪莹, 等. 杀虫剂亚致死浓度对普通大蓟马繁殖的影响[J]. 应用昆虫学报, 2020, 57(2): 427 − 433. [13] CHARLENE J H, JUDITH H M. Sex ratio patterns and population dynamics of western flower thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) [J]. Environmental Entomology, 1992, 21(2): 322 − 330. doi: 10.1093/ee/21.2.322 [14] KATLAV A, NGUYEN D T, COOK J M, et al. Constrained sex allocation after mating in a haplodiploid thrips species depends on maternal condition [J]. Evolution, 2021, 75(6): 1525 − 1536. doi: 10.1111/evo.14217 [15] WONDIMAGEGN A W, MÁRTA L, JÓZSEF F. Effect of temperature on the sex ratio and life table parameters of the leek-(L1) and tobacco-associated (T) Thrips tabaci lineages (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) [J]. Population ecology, 2021, 63(3): 230 − 237. doi: 10.1002/1438-390X.12082 [16] DALLAI R, DEL B G, LUPETTI P. Fine structure of spermatheca and accessory gland of Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) [J]. International Journal of Insect Morphology and Embryology, 1996, 25(3): 317 − 330. doi: 10.1016/0020-7322(95)00018-6 [17] LI X W, JIANG H X, ZHANG X C, et al. Post-mating interactions and their effects on fitness of female and male Echinothrips americanus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), a new insect pest in China [J]. PLoS ONE, 2014, 9(1): e87725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087725 [18] KRUEGER S, MÜLLER B, MORITZ G. Olfactory and physical manipulation by males on life-history traits in Echinothrips americanus Morgan 1913 (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) [J]. Journal of Applied Entomology, 2020, 144(1/2): 64 − 73. [19] KING B H. Sex ratio responses to other parasitiod wasps: Multiple adaptive explanations [J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 1996, 39(6): 367 − 374. doi: 10.1007/s002650050302 [20] ODE P J, ANTOLIN M F, STRAND M R. Constrained oviposition and female-biased sex allocation in a parasitic wasp [J]. Oecologia, 1997, 109(4): 547 − 555. doi: 10.1007/s004420050115 [21] KING B H. Sex ratio response to conspecifics in a parasitoid wasp: test of a prediction of local mate competition theory and alternative hypotheses [J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 2002, 52(1): 17 − 24. doi: 10.1007/s00265-002-0492-0 [22] KING B H, D’SOUZA J A. Effects of constrained females on offspring sex ratios of Nasonia vitripennis in relation to local mate competition theory [J]. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 2004, 82(12): 1969 − 1974. doi: 10.1139/z05-006 [23] METZGER M, BERNSTEIN C, DESOUHANT E. Does constrained oviposition influence offspring sex ratio in the solitary parasitoid wasp Venturia canescens? [J]. Ecological Entomology, 2008, 33(2): 167 − 174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2311.2007.00953.x [24] HENTER H J. Constrained sex allocation in a parasitoid due to variation in male quality [J]. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 2004, 17(4): 886 − 896. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00746.x [25] BOIVIN G. Sperm as a limiting factor in mating success in Hymenoptera parasitoids [J]. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 2013, 146(1): 149 − 155. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2012.01291.x [26] CHIRAULT M, BRESSAC C, GOUBAULT M, et al. Sperm limitation affects sex allocation in a parasitoid wasp Nasonia vitripennis [J]. Insect Science, 2019, 26(5): 853 − 862. doi: 10.1111/1744-7917.12586 [27] SIMMONS LW. Sperm competition and its evolutionary consequences in the insects[M]. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2001: 277-318. [28] AVILA F W, SIROT LK, LAFLAMME B A, et al. Insect seminal fluid proteins: Identification and function [J]. Annual Review of Entomology, 2011, 56: 21 − 40. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144823 [29] AVILA F W, SÁNCHEZ-LÓPEZ J A, MCGLAUGHON J L, et al. Nature and functions of glands and ducts in the Drosophila reproductive tract[M]//COHEN E, MOUSSIAN B (eds.). Extracellular Composite Matrices in Arthropods. Cham: Springer, 2016: 411-444. [30] THOMAS M L. Detection of female mating status using chemical signals and cues [J]. Biological Reviews, 2011, 86(1): 1 − 13. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00130.x [31] AYASSE M, PAXTON RJ, TENGÖ J. Mating behavior and chemical communication in the order Hymenoptera [J]. Annual Review of Entomology, 2001, 46: 31 − 78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.31 [32] XU H, ZHOU G, DÖTTERL S, et al. The Combined use of an attractive and a repellent sex pheromonal component by a gregarious parasitoid [J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 2019, 45(7): 559 − 569. doi: 10.1007/s10886-019-01066-4 [33] SCHIESTL F P, AYASSE M. Post-mating odor in females of the solitary bee, Andrena nigroaenea (Apoidea, Andrenidae), inhibits male mating behavior [J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 2000, 48(4): 303 − 307. doi: 10.1007/s002650000241 [34] FISCHER C R, KING B H. Inhibition of male sexual behavior after interacting with a mated female [J]. Behaviour, 2012, 149(2): 153 − 169. doi: 10.1163/156853912X631974 [35] BENELLI G, GIUNTI G, MESSING R H, et al. Visual and olfactory female-borne cues evoke male courtship in the aphid parasitoid Aphidius colemani Viereck (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) [J]. Journal of Insect Behavior, 2013, 26(5): 695 − 707. doi: 10.1007/s10905-013-9386-4 [36] MOWLES S L, KING B H, LINFORTH R S T, et al. A female-emitted pheromone component is associated with reduced male courtship in the parasitoid wasp Spalangia endius [J]. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(11): e82010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082010 [37] KRUEGER S, MORITZ G, LINDEMANN P, et al. Male pheromones influence the mating behavior of Echinothrips americanus [J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 2016, 42(4): 294 − 299. doi: 10.1007/s10886-016-0685-z [38] AKINYEMI A O, KIRK W D J. Experienced males recognise and avoid mating with non-virgin females in the western flower thrips [J]. PLoS ONE, 2019, 14(10): e0224115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224115 [39] AKINYEMI A O, SUBRAMANIAN S, MFUTI D K, et al. Mating behaviour, mate choice and female resistance in the bean flower thrips (Megalurothrips sjostedti) [J]. Scientific Reports, 2021, 11(1): 14504. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93891-5 [40] KRUEGER S, WILFER A, TSCHUCH G, et al. First detection of a female‐specific volatile substance in thrips[C]//Entomologentagung/Entomology Congress 2019. Halle (Saale): Deutsche Gesellschaft für allgemeine und angewandteEntomologiee. V. , 2019: 108. [41] KIRK W D J, DEKOGEL W J, KOSCHIER E H, et al. Semiochemicals for thrips and their use in pest management [J]. Annual Review of Entomology, 2021, 66: 101 − 119. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-022020-081531 [42] 李晓维, 罗雪君, 王丽坤, 等. 普通大蓟马聚集信息素的分离和鉴定[J]. 昆虫学报, 2019, 62(9): 1017 − 1027. [43] LIU P, QIN Z, FENG M, et al. The male-produced aggregation pheromone of the bean flower thrips Megalurothripsusitatus in China: Identification and attraction of conspecifics in the laboratory and field [J]. Pest Management Science, 2020, 76(9): 2986 − 2993. doi: 10.1002/ps.5844 [44] NIASSY S, TAMIRU A, HAMILTON J, et al. Characterization of male-produced aggregation pheromone of the bean flower thrips Megalurothrips sjostedti (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) [J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 2019, 45: 348 − 355. doi: 10.1007/s10886-019-01054-8 -

下载:

下载: